One of the most memorable questions I’ve been asked on a job interview was “So, how comfortable are you training walruses?” It was 1990. I was sitting in a conference room at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium in Tacoma, Washington. I’d flown there the previous night on a red-eye from Hawaii, where I was working as a dolphin trainer for the U.S. Navy’s Department of Defense. Though I’d trained other pinniped species (sea lions and harbor seals), I’d never even seen a walrus “in person” until that day. And what I saw wasn’t pretty. The zoo’s 10-year-old male walrus, named E.T., was a huge, smelly, ornery bully.

One of the most memorable questions I’ve been asked on a job interview was “So, how comfortable are you training walruses?” It was 1990. I was sitting in a conference room at the Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium in Tacoma, Washington. I’d flown there the previous night on a red-eye from Hawaii, where I was working as a dolphin trainer for the U.S. Navy’s Department of Defense. Though I’d trained other pinniped species (sea lions and harbor seals), I’d never even seen a walrus “in person” until that day. And what I saw wasn’t pretty. The zoo’s 10-year-old male walrus, named E.T., was a huge, smelly, ornery bully.

In response to the curator’s question, though, I said, “Oh, I’d be thrilled to have the opportunity to work with such a majestic species” or some such nonsense. After all, I wasn’t a complete idiot. I wanted the job of marine-mammal keeper and I knew that meant I’d have to wrangle walruses. Well, I got the job but soon began having nightmares that jolted me awake in a cold sweat: I was certain E.T. was going to kill me.

This fear was not as far-fetched as it sounds. Statistics from the Department of Labor indicate that in a typical year, one or more elephant keepers die at the hands (or, more accurately, feet or trunk) of their charges. And E.T., while not as big as an elephant, weighed nearly two tons. He had a track record, too. In previous years, two harbor seals that shared his exhibit had been found dead of somewhat unnatural causes. E.T. also had a habit of destroying his exhibit; he cracked the gunite surface, bent window frames and beat on the large metal gate.

To round out this charming personality profile, E.T. frequently masturbated in front of the underwater viewing window. Keep in mind that at this time he was approximately 10 feet long from whiskers to rear flippers. I’ll let you do the arithmetic, but suffice it to say that this was quite a shocking sight. Elementary school teachers on class field-trips to the zoo avoided the walrus exhibit like the plague.

When he first arrived at the zoo, E.T. was just a pup. A worker on an oil rig in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska had found him on the ice, orphaned and emaciated. He was flown to Point Defiance Zoo & Aquarium for rehabilitation, and there he thrived. His keepers regularly played and swam with him. They conducted daily hands-on training sessions. Soon, though, he grew up (and out!). Hormones surged and adolescence blossomed. E.T.’s trainers stopped entering the exhibit to work with him. His unpredictable aggression simply made it too great a risk to the keepers’ safety.

Within months of my arrival at PDZA, two other experienced marine-mammal trainers joined the staff. We resolved that we had to do something to improve E.T.’s life, both for his sake and that of the zoo’s visitors.

Convinced that much of E.T.’s misbehavior resulted from boredom and loneliness, we decided that we needed to begin making his food-delivery contingent on some behaviors we could live with. No longer would his daily diet of over 100 pounds of fish, squid and clams be given to him “for nothing.” If training time was limited on a particular day, E.T.’s food was stuffed into very large (~3-foot-long) PVC “feeder tubes.” These environmental enrichment devices served as food puzzles for E.T., who would suck his fish and squid through small holes we had drilled into the side of the hard plastic tubes.

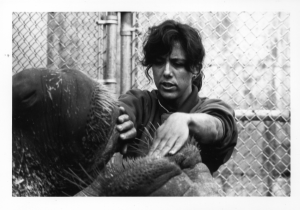

We began scheduling two or three daily training sessions, each lasting anywhere from 5 – 30 minutes. In the early stages, most of this training was conducted from a distance. The trainers remained behind a barrier (e.g., fence or railing), out of harm’s way, and used a long target pole to guide E.T.’s movements. Elephant keepers in zoos across the country commonly use this technique, referred to as protected contact. Using successive approximations, we were able gradually to get closer to E.T., always alert for any warning signs of aggression.

We limited the number of trainers authorized to work with E.T. Other marine mammals at the zoo had many trainers, some relatively inexperienced. Restricting E.T.’s trainers to three veteran staff members helped maintain consistency of behavioral criteria and fostered bonding between the walrus and his human teachers.

Dozens of behaviors were shaped or captured, using food as the most common unconditioned reinforcement, and the spoken word “Good” as the conditioned reinforcement. The only aversives used in E.T.’s training program were negative punishments such as temporary removal of attention or food. While many of these trained behaviors were silly — what we humans would call “tricks” (e.g., waving flippers, dancing and playing the harmonica) – others were a critical component of E.T.’s health care. These were referred to as husbandry behaviors, and were the core of our training efforts. One example was training E.T. to open his mouth on cue and to hold it open while a trainer used a dental scraper to clean plaque from his teeth. As a young walrus, E.T. had to have his tusks removed because they became badly infected. We were determined to prevent any further tooth loss, and so dental hygiene became a part of his routine.

The most incredible example of a husbandry behavior, though, involved taking a blood sample from E.T. We thought that if only we could obtain a blood sample, we could check his health more thoroughly than ever before and also collect information about the variability of his testosterone level during different seasons. But in order to take the sample, we had to insert a wide, long needle in E.T.’s back, next to his spine. And we had to do this while E.T. was unrestrained because we had nothing strong enough to hold down this now +3400 pound walrus. We knew it was important to set challenging goals for us and for E.T., though. If we were going to take the time to attempt to modify his problem behaviors, we didn’t want to sell him short in the process.

The shaping progression was a very gradual one. Steps along the way included simply touching E.T.’s back, massaging it, poking it with the tip of a paper clip and spraying it with rubbing alcohol. After nearly three years of desensitization and successive approximations, we held our breaths and inserted the giant needle. As the blood began to fill the tube, E.T. held still, but the trainers and other staff let out a cheer. I had tears in my eyes. All our work had paid off. E.T. was a totally different critter: gentle, compliant, attentive and awesome.

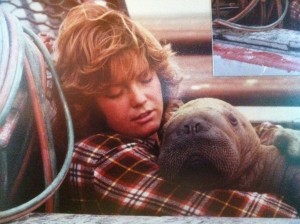

The change in E.T.’s overall behavior during those few years was nothing short of miraculous. It’s difficult to convey in words, but E.T. turned out to be one of the most extraordinary animals I’ve ever had the privilege to train. He enjoyed the training game so much that it was a challenge for us to devise new behaviors to teach him. He soon knew more than 80 behaviors on cue, including one that required him to position his head along the edge of his exhibit so that visiting children could touch his whiskers! He’d become the darling of the zoo, no longer X-rated.

The change in E.T.’s overall behavior during those few years was nothing short of miraculous. It’s difficult to convey in words, but E.T. turned out to be one of the most extraordinary animals I’ve ever had the privilege to train. He enjoyed the training game so much that it was a challenge for us to devise new behaviors to teach him. He soon knew more than 80 behaviors on cue, including one that required him to position his head along the edge of his exhibit so that visiting children could touch his whiskers! He’d become the darling of the zoo, no longer X-rated.

When I quit my job five years after that initial interview, my heart broke saying goodbye to E.T. We’d become friends who trusted each other, quite literally, with our lives.